- Nutritional benefits of maternal fish consumption outweighed the risk of neurologic deficits associated with mercury.

- The better neurobehavioral performance observed in infants with higher mercury biomarkers should not be interpreted as a beneficial effect of mercury exposure, which is clearly neurotoxic.

- Better neurobehavioral performance in mercury-exposed infants likely reflects the benefits of polyunsaturated fatty acid intake associated with fish consumption.

- Polyunsaturated fatty acid intake has been shown to benefit attention, memory, and other areas of development in children.

The nutritional benefits to infants of maternal fish consumption appear to outweigh the risks posed by the mercury contained in fish (Figure 1). The findings are the result of a prospective trial of 344 infants conducted at the University of Cincinnati Children's Hospital (UCCH) Medical Center in Ohio. The results were published recently in Neurotoxicology and Teratology.

The paper, enticingly titled “Low-level gestational exposure to mercury and maternal fish consumption: Associations with neurobehavior in early infancy,” reports on this trial that arrived at this controversial conclusion. The authors noted that, “Studies examining the effects of low-level gestational methylmercury exposure from fish consumption on infant neurobehavioral outcomes in the offspring are limited and inconclusive. Our objective was to examine the effects of low-level gestational exposure to methylmercury on neurobehavioral outcomes in early infancy.”

To examine the relationships among maternal fish consumption, gestational mercury exposure to fetus, and early neurobehavior in infants, the researchers assessed neurobehavior of 344 infants at 5-weeks using the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS). The researchers measured gestational mercury exposure as whole blood total mercury (WBTHg) in maternal and cord blood. “We collected fish consumption information and estimated polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) intake. We examined the association between gestational mercury exposure and NNNS scales using regression, adjusting for covariates,” they noted.

The Controversy

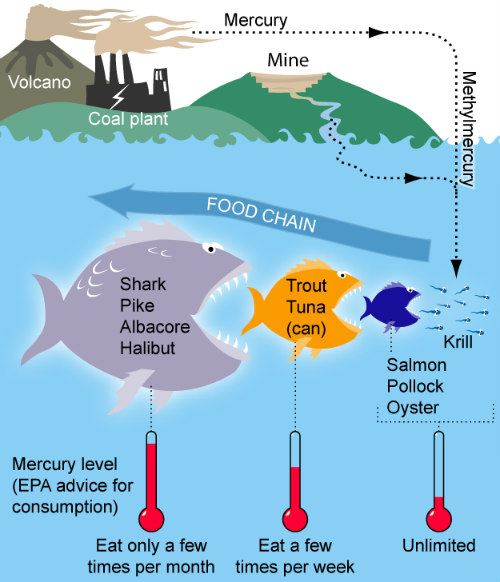

The issue is controversial largely because fish contains nutrients that are important for developing fetuses. Pregnant women are regularly advised to eat 2 or 3 servings of fish per week. However, today, varying levels of mercury are contained nearly all fish. This puts mothers to be in a quandary. This study appears to give them a way out: The nutritional benefits of fish outweigh the neurologic risks of mercury.

Importantly, the amounts of mercury contained in fish varies significantly by species. For instance, fish with low mercury levels include catfish, cod, pollock, salmon, shrimp, light canned tuna, and tilapia. Fish considered to contain high levels of mercury include mackerel, shark, swordfish, and tilefish. (Figures 2 and 3.)

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mercury may have toxic effects on the nervous, digestive and immune systems, and also on the lungs, kidneys, skin and eyes. Mercury is among the top-10 chemicals that are of major public health concern, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). However, results from the latest study yielded little evidence of harm in newborns whose mothers consumed low amounts of fish and who had low exposure to mercury.

"The better neurobehavioral performance observed in infants with higher mercury biomarkers should not be interpreted as a beneficial effect of mercury exposure, which is clearly neurotoxic,” explained lead author Kim Yolton, PhD, in a UCCH press release. “It likely reflects the benefits of polyunsaturated fatty acid intake that also comes from fish and has been shown to benefit attention, memory and other areas of development in children," she explained.

"The important thing for women to remember is that fish offers excellent nutritional qualities that can benefit a developing baby or young child," Dr. Yolton added. "Moms just need to be thoughtful about which fish they eat or provide to their child." Dr. Yolton is a Research Professor of Pediatrics at UCCH.

The Analysis

The researchers measure the geometric mean concentrations of WBTHg in maternal and cord blood as 0.64μg/L and 0.72μg/L, respectively. The majority of mothers (84%) reported eating fish during pregnancy. However, Infants with higher prenatal mercury exposure showed increased asymmetric reflexes among girls (P=0.04 for maternal WBTHg and P=0.03 for cord WBTHg). These same infants required less special handling during the assessment (P=0.03 for cord WBTHg), and demonstrated a trend toward better attention (P=0.054 for both maternal WBTHg and cord WBTHg), the researchers reported.

Infants born to mothers who consumed more fish consumption or estimated PUFA intake also had increased asymmetric reflexes and less need for special handling. In models simultaneously adjusted for WBTHg and fish consumption, or estimated polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) intake, the previously observed WBTHg effects were attenuated. Higher fish consumption or PUFA intake was significantly associated with less need for special handling.

Conclusions

“In a cohort with low level mercury exposure and reporting low fish consumption, we found minimal evidence of mercury associated detrimental effects on neurobehavioral outcomes during early infancy. Higher prenatal mercury exposure was associated with more frequent asymmetric reflexes in girls. In contrast, infants with higher prenatal mercury exposure and those whose mothers consumed more fish had better attention and needed less special handling, which likely reflect the beneficial nutritional effects of fish consumption,” the authors explained.